General Montgomery takes over Command August 1942

Len Moore fought with the 2nd Battalion Kings Royal Rifle Corps 2/KRRC across the deserts of North Africa during WW2 from 1941 to 1943. In August 1942 General Bernard Montgomery took over overall command of the 8th Army.

Len Moore 2nd Battalion Kings Royal Rifle Corps

General Montgomery was now appointed to command 8th Army. Though a more generous acknowledgement of the efforts of those who had borne the brunt for the last two years, and of his fortune to arrive as effective equipment flowed in, would have been welcome to the older desert regiments and formations, his incisive and confident touch was instantly felt throughout his Army. Concentrating his H.Q. by the sea with that of the Desert Air Force, he started planning his autumn offensive, while awaiting any renewed advance that Rommel might try.

General Bernard Montgomery in his M3 Grant tank Aug 1942 in the North African Desert.

KRRC Colour Sergeant Major shoots down a ME 109

The British defences were growing daily as belts of minefields were laid, and our attention must switch to the southern third of the front where both our battalions were now deployed; the 1st had moved down from Ruweisat to Himeimat on 3 August to join 4th Light Armoured Brigade, after CSM Clark of C Company had rounded off July's series of actions by shooting down a Me 109. There the 2nd Battalion had been enduring heat and flies in quantities never before seen: For the whole of July and most of August, the 7th Motor Brigade was operating at the southern end of Alamein line between the Ruweisat Ridge and the Qattara Depression.

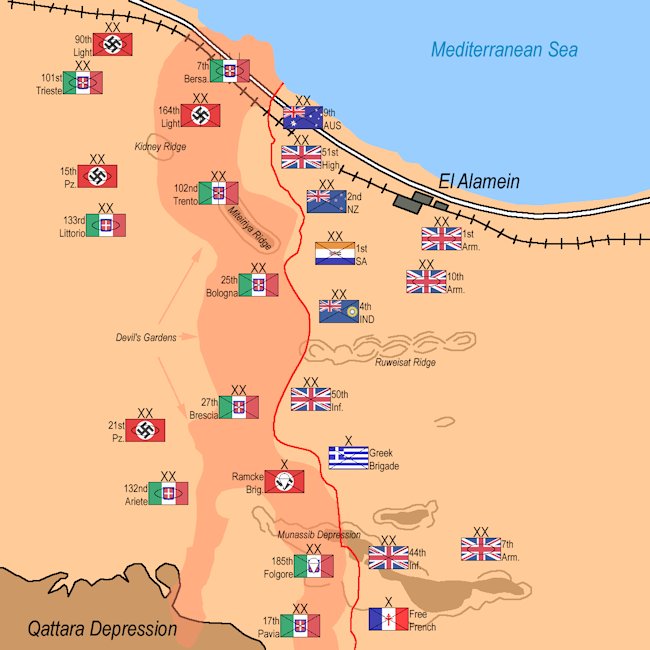

Map of El Alamein Aug 1942 in the North African Desert. The KRRC were at the bottom section of the line.

During this period there were many minor patrol actions and the battalion was continually engaged in harassing the enemy. The task given the columns was to 'engage and delay an enemy advance with maximum effort, but if attacked by major forces they will not become so committed that they cannot extricate themselves. If forced to withdraw by local enemy action, columns will withdraw due south keeping contact.' Although not spectacular, these operations were a continual strain, and fighting in the desert in the middle of the Egyptian summer was an ordeal both to man and vehicle.

There was also an increasing number of casualties, both from enemy action and sickness. On 4 July, the Intelligence Officer, Lt R. J. Brewis, received fatal wounds from shelling whilst operating his wireless set.

Flies, flies, flies !

Never have I seen so many flies as there were during the months of July and August, 1942, in the southern end of the Alamein line. One's whole horizon was bounded by flies, from the time when the first one settled on one's nose at first light until darkness brought blessed relief from the buzzing horde.

Some people said it was a plague which had drifted west from Egypt but wherever they had come from they had come to stay.' Eating became a battle and sleeping during the day was an impossibility. The flies were particularly attracted by liquid and to put down a mug of tea was sufficient to draw a crawling mass of flies, some of which would invariably drown themselves. Everyone made caps for their mugs out of ration tins and it was only by keeping these in place that one prevented one's tea from becoming a mess of drowned flies.

In this plague of flies the 7th Motor Brigade settled down to perfect its defensive positions in expectation of a further onslaught by the Germans. Deir El Munassib was a shallow depression in the desert, some two miles in length and 800 yards wide at its broadest point. The Battalion's positions lay astride the western end of the depression, where the low escarpment provided concealment from the enemy observers. To our north was the 2nd Battalion Rifle Brigade and beyond them were the strong positions of the New Zealand Division. To our south, covering the gap as far as Himeimat, a tall conspicuous peak, were the mobile forces of 4th Light Armoured Brigade, which included the 1st Battalion KRRC.

Across our front the Sappers began to lay a minefield and three of our companies were dug in on a wide front covering it. It was a curious mixture of static and mobile warfare. The forward Companies remained in their positions every night but all their vehicles were tucked in under the escarpment ready for use. 2nd Battalion HQ and the 25-pounder Battery, on the other hand, moved back every night to the eastern end of the depression.

British Tommy on sentry duty in the desert amongst knocked out Humber and Bedford truck wrecks

Mum it aint half hot out here!

During the long hot days, when the Riflemen sweated, swore and cooked their meals, the Germans did little to add to our discomforts. They too must have been swatting and cursing the flies. A good two miles lay between us and the German positions and this area was dominated by our Gunner O.P.'s. Every morning before dawn the FOO's used to go out through the minefield with their mobile escorts of carriers and anti-tank guns and spend the day sniping at anything they saw and that was little enough. Later on in August a few enemy patrols came down to recce our minefields, but they were, for the most part, seen off by our standing patrols.

On 24 August, 1942, Lt-Col W. Heathcote-Amory took over command of the Battalion from Lt-Col O. N. D. Sismey. Both had been with the Battalion since leaving England and the latter was to continue in command until after the Normandy D Day in 1944. By now there were increased signs of enemy activity and it was obvious that Rommel was about to launch his final, all out attempt to reach the Delta.